October 2020 has been a productive month for Watershed Cairns. We published a book of forty-five-images from the Upper Mississippi River and made fifty-six-mages on the Ohio River from its mouth at Paducah, Kentucky to its source at Pittsburg,, Pennsylvania. Take that, Pandemic!

Missouri History Museum Plastic Trash

Missouri History Museum Curator of Environmental Life David Lobbig penned this article about a few of the revealing artifacts in the current Muddy Mississippi River exhibit. He mentions “Plastic Trashin’ sculpture by Libby Reuter.

Marking TIme

Mighty Mississippi displays an epic history, but dozens of exhibit topics remain “on the cutting room floor.” Even with a 6,000 square foot gallery, the teaser for more recent story elements was edited out: Technology enabled the first people’s success in North America’s greatest watershed. This statement illuminates our present episode of an ongoing drama, as human technology threatens all the valley’s actors, and even the stage set itself.

More than 11,000 years ago, the last Ice Age finally thawed as glacial sheets retreated toward the north pole. In the beginning of the relatively warm Holocene, the geological epoch when all human existence has elapsed, the continent’s center ran rich with glacial meltwaters. Rivulets sought channels, uniting to form an ancient Mississippi River. Abundant, flowing freshwater produced tremendous variety and richness of life, and attracted people. Enormous bears, wolves, and other giant mammals roamed the landscape. Mammoths and mastodons, hairy ancestors of elephants, were among those hunted by Native Americans. Based on evidence discovered in other parts of this continent, uneaten carcasses were probably weighted down and sunk into cool backwater pools and lakes to protect and preserve future meals. Uniquely shaped stone spearpoints are the scant testimony to this period, when advanced skills refined chert cobbles into specialized weapons. Many of these sleek, delicate, and durable Clovis-like points have been found throughout the Mississippi River valley.

Today’s contrasting artifacts are the thousands of plastic products annually ejected into the watershed. The Mississippi River system is a conduit for tons of bottles and other one-time-use containers since the mid-20th century. These, and microparticles from them, will be around for thousands of years, just as Clovis points have been. Unlike a stone’s mineral composition, molecules that make up plastic do not readily break down into parts from which life is constructed: plants and animals do not use plastic to grow and survive, but instead their metabolic, reproductive, and developmental processes are often damaged by them. Just as our society is rapidly warming global climate and we are driving many species to extinction, these engineered chemicals mark the Mississippi River valley during the Anthropocene epoch, a time beginning now, as our culture’s technology abruptly changes the geological record.

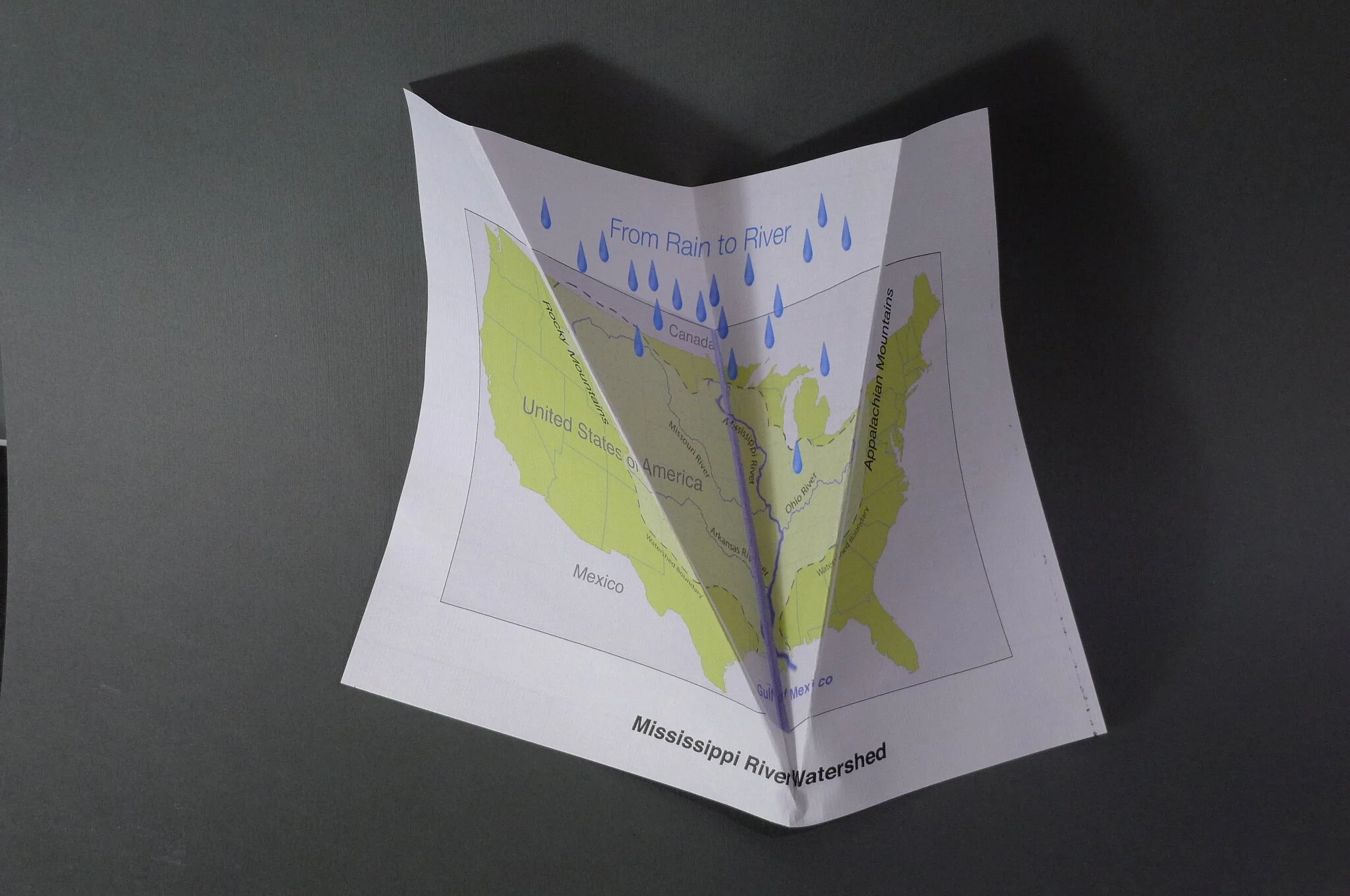

WaterSHED

Working on a series of one minute and 15-second videos to explain "wateshed". This is a still from te second "Minute”

Dubuque Museum virtual artists talk

The Flow exhibit remained closed due to the stay-at-home COVId precautions, but concluded with this video artists talk https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5G44ksNurZw&feature=youtu.be.

Stacy Peterson and the Dubuque Museum of Art staff were great to work with on installing and all the effort to prepare images and the technical aspects of this, their first video talk. The four artists represented the region , Anna Metcalfe, Minneapolis, Minnesota;Jennifer Lynn Bates, Cedar Falls, Iowa ; Susan Knight, Omaha, Nebraska: and Missouri ( that’s Watershed Cairns) and different views of the river and ways of involving the viewers.

Anna Metcalfe used ceramic cups glazed with the stories people wrote about their experiences with the river at community tea parties. Many of the cups featured stories that Dubuque residents wrote at their tea Party last summer. Jennifer Lynn Bates created a large wall map of the river at Dubuque, with recycled plastic water bottles that she painted to to represent the levels of pollution in the river. Susan Knight’s work (on the right in this photo)involved layers of cutout and sometimes painted plastic to represent the currents deep under water.

Libby represented Watershed cairns and talked about the cairns and images from the Uppet Mississippi RIver that were in the exhibit. I was pleased to learn from Stacy’s introduction that the proposal for our Watershed Cairns traveling show was the impetus for this exhibit. Marketing occasionally bears fruit.

St. Louis Regional Watershed Map

This map of eastern Missouri and western Illinois focuses on the streams and rivers that form the confluence of the Missouri, Illinois, and Mississippi Rivers. This is the heart of the Mississippi River watershed. With maps and travel directions on our phones, it may seem silly to make another map. But, highway and Google maps emphasize roads and minimize rivers.. Most rivers are almost imperceptible thin blue lines on these maps. To make our essential fresh water system visible, I created a 24-inch square map using the United States Geological Survey National Map. https://viewer.nationalmap.gov/advanced-viewer/ .

I selected the USGS Hydrocached base map (window icon). I turned on the Transportation Layer and selected Labels and Features from the Layers (stack Icon). I used level 11 magnification and captured a grid of images, “printing “ them to the site and then saving them on my desk top. I imported more than 20 of these maps as layers in Photoshop and matched them to each other creating the large map. I didn’t select the city names, because that made the map too cluttered, instead, I typed and placed selected city names to help viewers find their place on the watershed. You won’t see any town names on the map I have posted here.. I ommited the type layer on this print because even the fewer names distracts from the streams.

Dubuque Museum of Art Update

The Flow exhibit including the Watershed Cairns work closed March 17 for the public’s safety during the Carona virus. and the exhibit has been extended until May 17. Hopefully, the Museum will be able to open and give more people a chance to see the work. Stay well, everyone.

Which river span is next?

The yellow pins on this Google Map show most of the sites* where we have created Watershed Cairns images. They dot the land near the Yellowstone River, a major tributary to the Missouri River, and from the Missouri’s origin in northern Montana. A second string of locations follow the Mississippi River from its origin at Lake Itasca, Minnesota, to the confluence of the Missouri and Mississippi rivers at West Alton, Missouri. (*There are many more sites in the St. Louis Metro area than are shown on this map.)

We originally planned to follow the Mississippi River south to the Gulf of Mexico this summer. However, the more we look at this map and think about the importance of the Ohio River to the watershed and to the quantity and quality of the Mississippi River water, we’re now thinking that we should follow the Ohio from its origin in smaller rivers of Pennsylvania and southwestern New York. Stay tuned.

Dubuque Museum of Art

The two Images on the left, Lily Pad and Coulee were created in the Dubuque, Iowa area.

Read MoreRusty Freeman Mighty Mississippi Essay

Rusty Freeman, visual arts director at the Cedarhurst Center for the Arts, shared these thoughts about the Trashin’ sculpture at the Missouri History Museum’s Mighty Mississippi River exhibit. Thank you Rusty.

The Mighty Mississippi, Missouri History Museum, St. Louis

The Missouri History Museum opened The Mighty Mississippi, a multi-media exhibition

benchmarking the myriad ways the great river formed the region’s differing historical cultures,

that at various times flourished, culminating with the city of St. Louis.

What caught the eye was a particular art work in the exhibit by St. Louis artist Libby Reuter and

how it functioned within the context of the exhibitions themes and goals. Reuter’s Trashin’

presents trash as aesthetic object. How might the use of garbage as aesthetic statement

relate to the exhibit?

The Mighty Mississippi exhibition features rich layers of social, cultural, economic, fine and

decorative arts, sociological, and geographical contexts all connected by specific

cartographies, chronologies, and ethnographies. Timelines begin with the Mounds people to

Native American and the European fur trade to today. Steamboats delivered the industrial age

and are a highlight of the exhibition. Information systems include wall texts, infographics,

paintings, photographs, historical documents and objects, maps from various eras, short

videos, ambient narration and sound effects, huge backlit illustrations, and hand-held audios.

The exhibition is a visually sumptuous, inviting, deep exploration and discovery site for

schoolchildren and adults alike. The Mighty Mississippi was organized by the museum’s David

Lobbig, Curator of Environmental Life, and a companion 308 page book, Great River City: How

the Mississippi Shaped St. Louis, lavishly illustrated, was written by Andrew Wanko, the

museum’s Public Historian. The exhibition and book drive the exhibition theme that the

Mississippi River should not be taken for granted.

The most contemporary of art installations greet visitors near the exhibit entrance installed

above in the rafters. It is an installation of approximately 500 items discarded into the

Mississippi and range from plastic food and beverages containers, tools, to toys.

Trashin’ is central to exhibit themes both for its aesthetics and historical connotations.

However, Trashin’ has a brief label noting only who picked up the trash (Living Lands & Water,

Open Space Council, Boys & Girls Clubs of Greater St. Louis, and volunteers). Trashin’ implies

that as the Mississippi shaped St. Louis, the river was shaped in return.

The aesthetics of refuse and garbage have a long lineage in art history. Picasso (Still Life with

Chair Caning, 1912), Duchamp (Fountain, 1917), Dadaists (1916-1922), Assemblage movement

(1960s), Betye Saar (1960s to today), Rauschenberg (second half of 20th century), Mierle

Laderman Ukeles (1970s to today), and Mark Dion (1980s to today) to cite only the prominent.

What trash as trash signifies as art is a host of social, political, cultural themes of recognition

and representation of ignored or repressed forms of life; the everyday, the no-longer-useful, the

unsavory, the unspeakable. Although The Paris Agreement is reported on, the mass media

does not broadcast much these days on the rampant and actual pollution of the planet.

However, for example, there are coordinated efforts to clean up the Great Pacific Garbage

Patch (there are five such “patches” in the world’s oceans). See theoceancleanup.com

According to the research scientists of The Ocean Cleanup rivers are a major source of plastic

waste flowing into the oceans. One thousand of the world’s rivers account for 80% of the

plastic in all oceans.

Although the Romans built clean water aqueducts and developed a separate waste water

system, these ideas evolved unevenly and sporadically worldwide. It was not until the 19th

century that connections were made to cholera and waste water. The critical understand of

sanitation is a recent development in human history.

As noted in Great River City, St Louis did not have a sewer system in 1849; waste went into the

streets, as it had for centuries around the world. Cholera killed 4,500 officially in St. Louis in

1849, with many more deaths of the poor not being recorded. The city’s first sewer was

completed in 1889. The sewer by custom emptied into the Mississippi. It was in 1871 that the

city for the first time had reliable drinking water for homes and businesses. However, a large

percentage of the city in the early 1900s still carried their water home from street corner

spigots. As late as 1904, drinking water from the Mississippi was muddy. In 1915, St. Louis

opened the largest filtration plant in the world. Only in 1972 did the Environmental Protection

Agency make it illegal for cities and industries to dump raw sewage into rivers.It is a recent turning point that humans collectively have begun to consider seriously how the Anthropocene has been affecting the environment.

The inclusion of Trashin’ was a bold gesture by the Missouri History Museum. The art

installation directly confronts a contemporary, timely, and serious issue regarding how we view

the world today. As Mark Dion has said, “Science tells us what things are, but art can express

how we as a society and as individuals feel about that.”

To the curators’ point, the Trashin’ art installation of debris from the Mississippi River connects

to the long history of artists using quotidian, banal objects from everyday life to put into play

statements in the public realm or social conversation. Like Duchamp’s Fountain, the aesthetic

function of Trashin’ works here, as it has in history, to present an object that is regarded as ugly

or disgusting or unworthy of contemplation. Trash is generally unspeakable, why bother? No

topic is off limits today, but, some topics are repressed and not discussed nearly enough, in

legislatures or schools. These unspeakable topics are repressed and end up functioning in the

background, always looming, rarely addressed, except by scientists, artists, or activists.

Climate change has been discussed worldwide, for years, yet, little has been accomplished.

Duchamp, I consider, wanted to put something unspeakable into the discussion of how art was

beginning to function in the early 20th century. The word urinal could not even be printed in

newspapers of the time. Duchamp opened the conversation to what art could address in

public, the unspeakable issues. Duchamp was not concerned with the aesthetics of plumbing,

but the monetarization of the work of art, and more importantly, with creating an irony of

indifference towards social customs and sparking new and different thinking about quotidian

objects presented as art. Like Fountain, Trashin’ functions more than a mere equivalence that this art signifies symbolically this social concern, although it does that, too. Trashin’ signifies materially; its

form is the meaning.

The Missouri History Museum curators by exhibiting Trashin’ within the all-important cultural

contexts of the Mississippi opens the conversation to issues both aesthetic and conceptual in

how we think and act today in regard to the world around us. The physical placement of Trashin’ analogizes the conundrum faced today with pollution worldwide, it is out of sight most of the time, a haunting structuring absence, long ignored, hanging just over our heads.

Libby Reuter is the organizer of Watershed Cairns, an art-centric enterprise developing

awareness and support for clean drinking water and the importance of keeping local

watersheds clean. Reuter and colleague Joshua Rowan, a St. Louis photographer, document

the bio-diversities of the Midwest’s watersheds, see watershedcairns.com. The Mississippi

watershed is the largest of North America.

Installation at Dubuque Museum Of Art

Libby installing a cairn at the Dubuque Museum of Art. The museum is in the heart of a vibrant downtown and has a great professional staff. It is honor to be part of this group exhibit, Flow. No pictures yet of the eight watershed cairns images also n the exhibit. The gallery staff was installing them when we had to leave to avoid a predicted a snow storm. Will post shots of the prints installed soon.

Dubuque Museum of Art

Watershed Cairns will have work in the Dubuque Museum Art Water into Art exhibit, January 18–April 19, 2020. The exhibit will include installations from Anna Metcalfe of Minnesota, Susan Knight of Nebraska, and Jennifer Bates of Iowa. The exhibit focuses on the relationship of art and science through the theme of water.

Soon we’ll be transporting eight prints and two cairns to the museum. The work includes four new prints. Lily Pad, 2017 (pictured with this post) and Coulee 2016were created in the Dubuque area on our trips marking the upper Mississippi River.

Libby will be participating in the Museum’s artists talk at 1:00 p.m on the last day of the exhibit, Sunday, April 19. If you are in the area and can come to the talk, please say Hi!

Trashin' Excepts from an Essay by Olivia Lahs-Gonzales

St. Louis-based artist Libby Reuter has made environmental advocacy an integral part of her art practice. Trashin’, seen in the exhibit The Mighty Mississippi at the Missouri History Museum,was created from detritus found along the river that was discarded on the land and washed into storm sewers, creeks and connecting rivers. We tend to take for granted the clean,plentiful water that comes from our taps, but pollution, aging infrastructure and droughts from climate change underscore how fragile our watershed really is.

A natural offshoot of WatershedCairns, a collaborative project by Libby Reuter and the photographer, Joshua Rowan, shown at the Missouri History Museum in 2014-2015, Trashin’ very directly and painfully illustrates the consequences of our rampant use of convenience plastics and our disregard for the natural environment and our watershed. Look closely at the sculpture, and you will see a multitude of plastic: drinking and motor oil bottles, bags and straws, Styrofoam packing materials and cups, pool floats, orphaned flip-flops, gas cans, a rake, the back end of a duck decoy and a cooler, all found in or near our local rivers.

To construct this sculpture, Reuter partnered with a number of environmental organizations including Operation Clean Stream, a program of the Open Space Council of St. Louis, Living Lands and Waters, and Missouri River Relief, who actively work to collect and properly dispose of trash that has found its way into our rivers. From their cleanup efforts, Reuter sourced the materials for the sculpture and worked with Missouri History Museum staff to build the mobile.

Trashin’ is linked to Watershed Cairns, an expansive collaborative project in which Reuter constructs beautiful sculptures by stacking household and antique glass vases, bowls and bottles into “cairns” (markers), which are placed in watershed sites along the Mississippi and Missouri rivers. Her creative partner Joshua Rowan, then documents these temporary installations in the landscape before they are removed, leaving no trace. The team uses the resulting photographs, which are beautiful works of art in themselves, and the sculptures to create exhibitions that are shown alongside educational texts about the Mississippi River basin and its plight. Collectively, this body of work calls attention to the sometimes hidden watersheds and their critical state, but it is also meant to instill an emotional connection with, and appreciation for, the beauty of the land.

To date, Reuter and Rowan have placed and photographed Cairns in over 300 locations across the Mississippi-Missouri River basin.Reuter’s sculpture Trashin’ is a call to action—to create an awareness of, and to improve our practices for our great waterways. The Mississippi-Missouri River basin is one of the world’s largest watershed regions, covering about 40 percent of the continental United States; serving irrigation for 92 percent of agricultural exports and providing 50 million people with fresh drinking water.

The watershed—its rivers, tributaries and creeks—are the veins of our central region. Everything we discard without care on our streets and our land eventually finds its way to the river and ultimately into our oceans where, as recent science has indicated, it breaks down into micro-plastic particles that end up in our food stream and, ultimately, in our bodies. Hanging above the viewer like a Sword of Damocles, Trashin’ reminds us all that we need to change our habits.

From an essay by Olivia Lahs-Gonzales. Olivia Lahs-Gonzales is an independent curator, writer and artist, based in St. Louis. She wasDirector of the Sheldon Art Galleries for seventeen years and Assistant Curator, and CuratorialAssistant in the Department of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs at the Saint Louis ArtMuseum for nine years. Lahs-Gonzales has exhibited her personal work in St. Louis, Chicago,London, Taipei and Tokyo.

Trashin' installed in the Mighty Mississippi gallery - October

Trashin’ being hoisted in place in October before the historic objects were installed

Read MoreClose-up showing a couple of strings of bottles and other plastic trash

close up of bottles and other plastic trash

Read MoreTrashin'

On Saturday, November 23, 2019, The Mighty Mississippi River exhibit will open at the Missouri History Museum, St. Louis. Watershed Cairns artist Libby Reuter was commissioned to create a large overhead sculpture from bottles, foam packaging-materials, and other non-biodegradable plastic that has been tossed onto the land, washing into storm sewers, creeks and rivers. Plastic litters riverbanks, harms marine life, affects the quality of our drinking water. And contributes to the trash floating in the Gulf of Mexico. Trashin’ contains only a small sample of the trash removed from parks and the Meramec and Mississippi rivers by volunteers for the Open Space Council, Operation Clean Stream, Missouri River Relief, Living Lands and Waters, and other volunteers in 2019. After washing the smaller plastic trash, Reuter and assistants (Amelia, Joshua, and Jamie) made over 100 two-to four-foot-long strings of bottles and objects including foam cups, footwear, toys, a gas can, mailbox, and tire swing. These were tied to a wire grid on three wooden frames that have been suspended from the Gallery ceiling. We won’t be able to photograph the sculpture until the over 200 historical objects are safely installed and lit, but will post when photos are available.

October on the Middle Mississppi

On October 23 and 24, we set out to make new work on the Mississippi River between St. Louis and St. Genevieve, Missouri. The first day was cloudy and the second, raining. Most of our images are from that first day. This one, Kaskaskia Levee, is a testament to what environmental philosopher Gary Snider writes about watersheds, “The surface [of the earth] is carved into watersheds…. The watershed is the first and last nation whose boundaries, though subtly shifting, are unarguable.”

The geographic history of Kaskaskia is a good illustration of this mutability. Kaskaskia was founded by Father Jacques Marquette in 1675, on the eastern bank of the Mississippi River. Later, the town was the capital of the Illinois Territory until Illinois became a state in 1818. Then in 1844, the Mississippi River flooded the town. When the water receded, the river had carved a new channel, and Kaskaskia was now on the Missouri side of the river, but still a part of the state of Illinois. Here, the cairn is resting atop a high levee that keeps the Mississippi River in its new channel-most of the time. A levee break north of town during the Great Flood of 1993 covered the town in nine feet of water.

Flag Over Water

Flag Over the River

May 5, 2019

Near the intersection of Orchard and Park Streets in Hardin, Illinois

39° 09’ 06” N 90° 37’ 05” W Elevation 440

The first image of the day was created on the Illinois River where it was expanding into the town of Hardin, Illinois. A block away, men were stacking sandbags to protect a house, and a popular riverside restaurant had a ring of sandbags around the parking lot and a temporary sign that read “carryouts only”.

Read More

On the Illinois River

As the flood of 2019 was reaching crests in towns along the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers, we set out to see what was occurring on the Illinois River north of its confluence with the Mississippi River, just north of Alton. For about 75 miles, the Illinois River runs parallel to the Mississippi, creating a wedge of agricultural land between the two rivers, 4.5 miles wide at the Hardin, Illinois in the south and 47.5 miles wide in the north at Quincy. As we drove north from Alton on Sunday, May 5, we saw the flood’s effect. Roads were closed (or should have been) because they were covered in water. Families were filling sandbags in the Meredosia City Park. Men were stacking sandbags to protect a house in Hardin, Illinois, not far from a popular riverside restaurant that already had a ring of sandbags around the parking lot and a sign, “carryouts only.” In Hillview, Illinois, the creek in the middle of town had receded after it overtopped its banks a few days earlier. We drove on gravel roads over levees separating agricultural land from the rivers and even more cautiously on roads that seemed to lead over the top of the levee to the valley below, only to be met by the swollen Illinois river on the other side.

Read MoreGetting Ready for the Lower Mississippi RIver

Evening light filters through one part of the new cairn in Libby’s studio. She is making a new series of sandblasted cairns in preparation for our journey on the lower Mississippi RIver. Beginning in May, we’ll pack these new cairns with parts of cairns that were used on the Upper Mississippi and Missouri rivers and follow the river to the Gulf of Mexico..

Read MoreMarch 2019 activites

In addition to the six large transparent images at the Lambert International Airport and the exhibit Art Marks: From Minnesota and Montana to the Confluence at the Bonsack Gallery, John Burroughs School, 755 Price Road, St. Louis, Missouri, 63124 through April 10, Watershed Cairns will be giving talks, and attending receptions,

Knowing our Place, a community discussion about our region between the Rivers, hosted by St. Fransican Sisters of Mary from 1:30 - 3:30 p.m. on Wednesday March 20, 2019 at the May Center on the SSM DePaul Hospital Campus, 12303 De Paul Drive, Bridgeton, MO 63044 will feature a talk by Watershed Cairns artist Libby Reuter, river story teller Dean Klinkenberg, and Missouri Coalition for the Environment water advocate Maisah Kahn. No charge, Reservations required. email rhutchins@fsmonline.org

Missouri Coalition for the Environment is hosting a special reception at the Bonsack Gallery from 2-4 on Sunday March 24. $20 tickets availablehttps://moenvironment.org/events2/cairns-exhibit

Libby Reuter will be presenting images of Watershed Cairns work on the Mississippi and Missouri River in her talk Where's the Water at 7 p.m., Wednesday March 27 at the Webster Groves Presbyterian Church, 45 W. Lockwood Avenue, Webster Groves, MO 63119. The public is invited. Admission is free, no registration required